Into the Blue: on The Pond by Adam Jeppesen

Danish marshlands are among some of the most impressive in the world. They are characterised by ethereal light and changeable weather, which is capable of transforming quagmire ponds from glistening jewels to eerie fens in a matter of moments. These marshy ponds are places where the cycle of life thrives in all of its stages; animals live and die, migrating birds pause in transit. The pond bears witness to all around it – life, death and decomposition – finally subsuming the physical matter of its environment. During this process the pond also collects history, memorialising its own vitality. There is a sense of contradiction that accompanies this churning consumption, driven by the persistent turn of nature’s cogs: the pond’s contents are invisible from the surface, clouded by its murky waters; its secrets cannot be discovered before one is beyond the threshold to the unknown – by which point it is too late to return to the banks.

In this, the natural world echoes human behaviours. Notions of society, identity and humanity have evolved in recent years at a rapid pace. However, this evolution has been tainted by polarisation and the distance between poles appears to be increasing with a stubborn surety. In an effort to make sense of attested societal contradictions, an interrogation of the human condition is underway that mimics nature’s processes in numerous ways. Decomposition is an embodiment of contradiction; it is transient permanence, transforming the dead into the ever-living without any promise of rebirth. Just as history promises an immortalisation of experience – and, indeed, photography promises an immortalisation of memory – decomposition promises an immortalisation of essence. Like sending daring divers into the pond, an examination of the human condition invokes a journey of discovery that seeks self-identity as well as collective experience. Adam Jeppesen’s exploration of the themes of transience, humanity and contradiction takes the pond out of place, transplanting the viewer into a comparable situation where nature is still king but human experience is key.

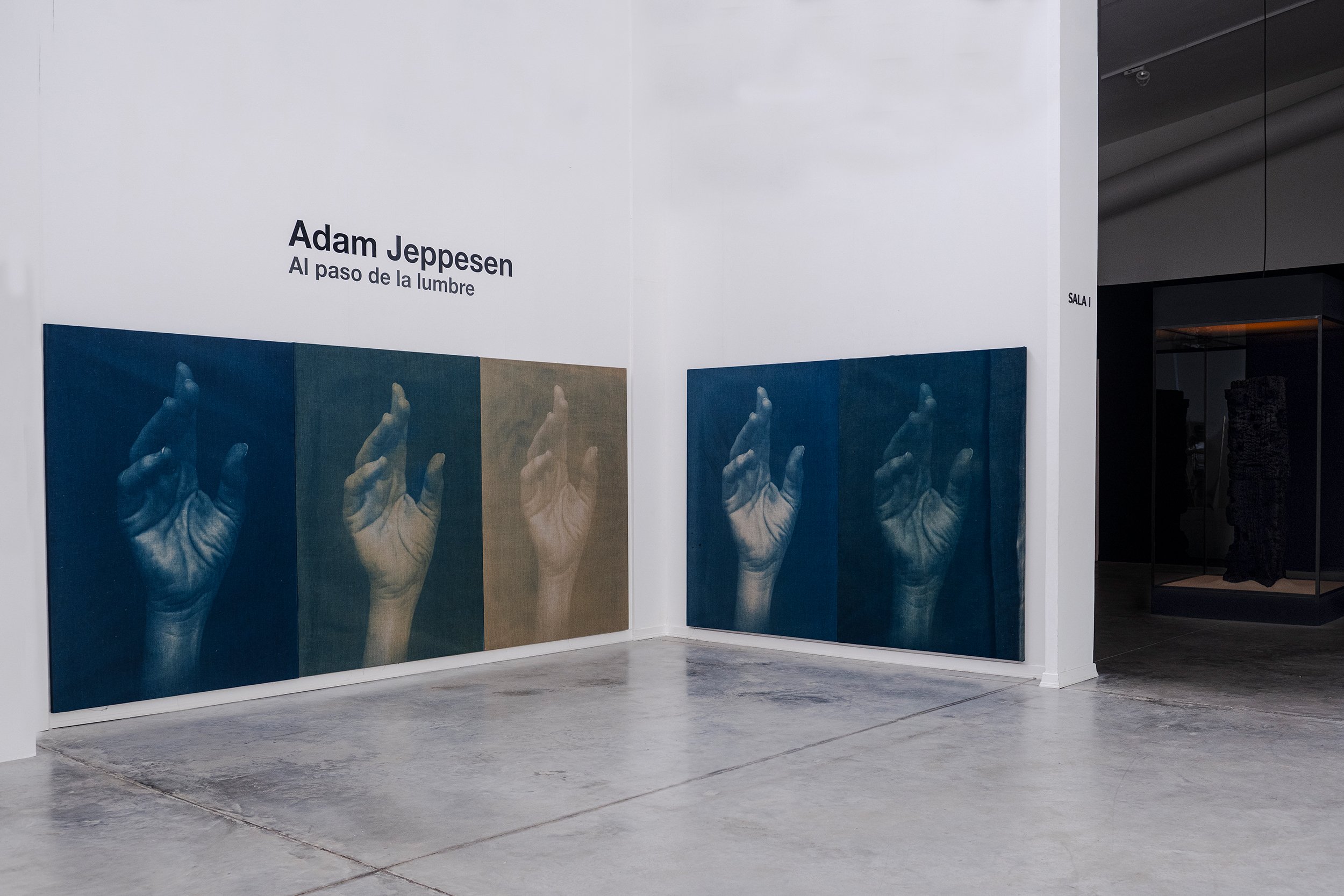

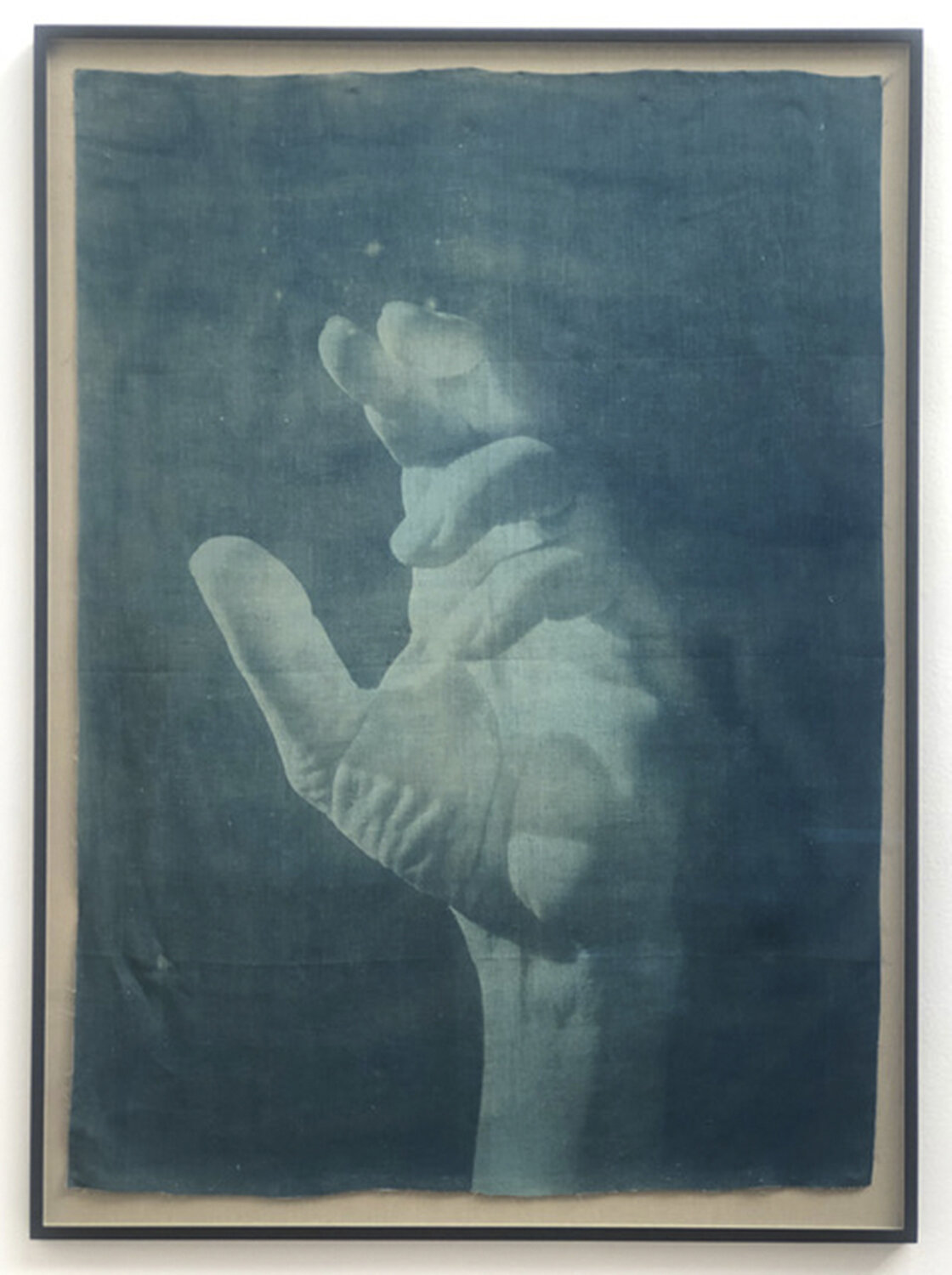

Jeppesen’s practice has long dealt with notions of identity and incongruity, going back to the renowned Flatland Camp Project. However, if that project was anchored in personal experience, The Pond situates individuality within broader notions of collectivism. The hand is the visual motif around which this series exists, and it is the prism through which the work can be understood; the symbolic currency of the hand allows for an interrogation of the self and wider mankind. Humans can never see themselves quite as they are in real life; faces, typically conveyors of character, are invariably filtered through waves of reflected or refracted light. However, hands are customarily visible in a direct, unadulterated view. They fashion the most authentic self-image, as intuitive instruments for expressing emotion and as tools that define human singularity through their deeply personal nuances of manner, movement and gesticulation. Hands are the loci of power, responsible for executing action; the tools of creation, as well as the arbiters of destruction. This duality is integral to The Pond: for whilst hands are self-signifiers, they are also universal; they are symbolic but incidental, ever-present yet overlooked in our peripheral consciousness. This is reminiscent of the contradictions of solitude, that core ingredient of human experience. There is a collective solidarity to solitude in the knowledge that humans enter and leave this world alone. Even in life, relationships are forged and communities are formed, but people remain instinctively solitary beings. In images from The Pond, which Jeppesen has described as ‘landscapes’, the universality associated with the motif of the hand is essential to eliciting the desired conceptual and emotional response; however, the specificity of the actual subjects is anecdotal. The importance lies not in the owner of each limb, rather in the relatable human experience such a subject is able to provoke.

The visual language of art has nurtured the motif of the hand and the quest for capturing a compelling likeness has endured throughout centuries of art history. The philosophical complexities associated with the symbol of hands are reflected in their physical form – comprising a delicate web of 29 bones, 123 ligaments, 34 muscles, 48 named nerves and 30 arteries – which has rendered them notoriously difficult to depict. During the Renaissance period, an artist’s talent was often judged by their ability to depict hands; the draughtsman’s pencil or the sculptor’s chisel laboured over the accuracy of their expression, and refined gestures were considered to be windows into the soul. Though Jeppesen employs the apparently more recordist medium of photography, his pictures are far from documentary. The deep blue colour imbues a melancholic feeling, at once hopeful and lamenting of what hands – hands of the present, hands of the past and hands of the future – are capable of. Hands signify the balance of control around human action; however, they also symbolise notions of destiny in that human action is informed by the flaws of human nature, only partially controllable by the tempering forces of rationality and mediation. Human emotions and behaviours are programmed to respond to essential instincts around protection, survival and legacy – reactions that are fundamentally unaccepting of the natural life cycle in which living beings are born, live, die and decompose. The natural world is the sustaining source of life, providing the vital ingredients for breath, growth and movement. After death, decomposition returns physical matter to nature, feeding back into the ecosystems in which that life participated. Humans consider themselves separate to the rest of the natural world in this regard, even oftentimes separate from each other, despite the fact that all living things are connected by physiological processes. From a micro-organism to a sprawling forest, everything evolves and absorbs or stands to be absorbed, betraying the inimitable forces of nature and time as the unmatched rulers of this world. In The Pond Jeppesen reminds us of this, emphasising a consciousness of time on a grander scale and encouraging a humbleness to the passage of life and its related encounters.

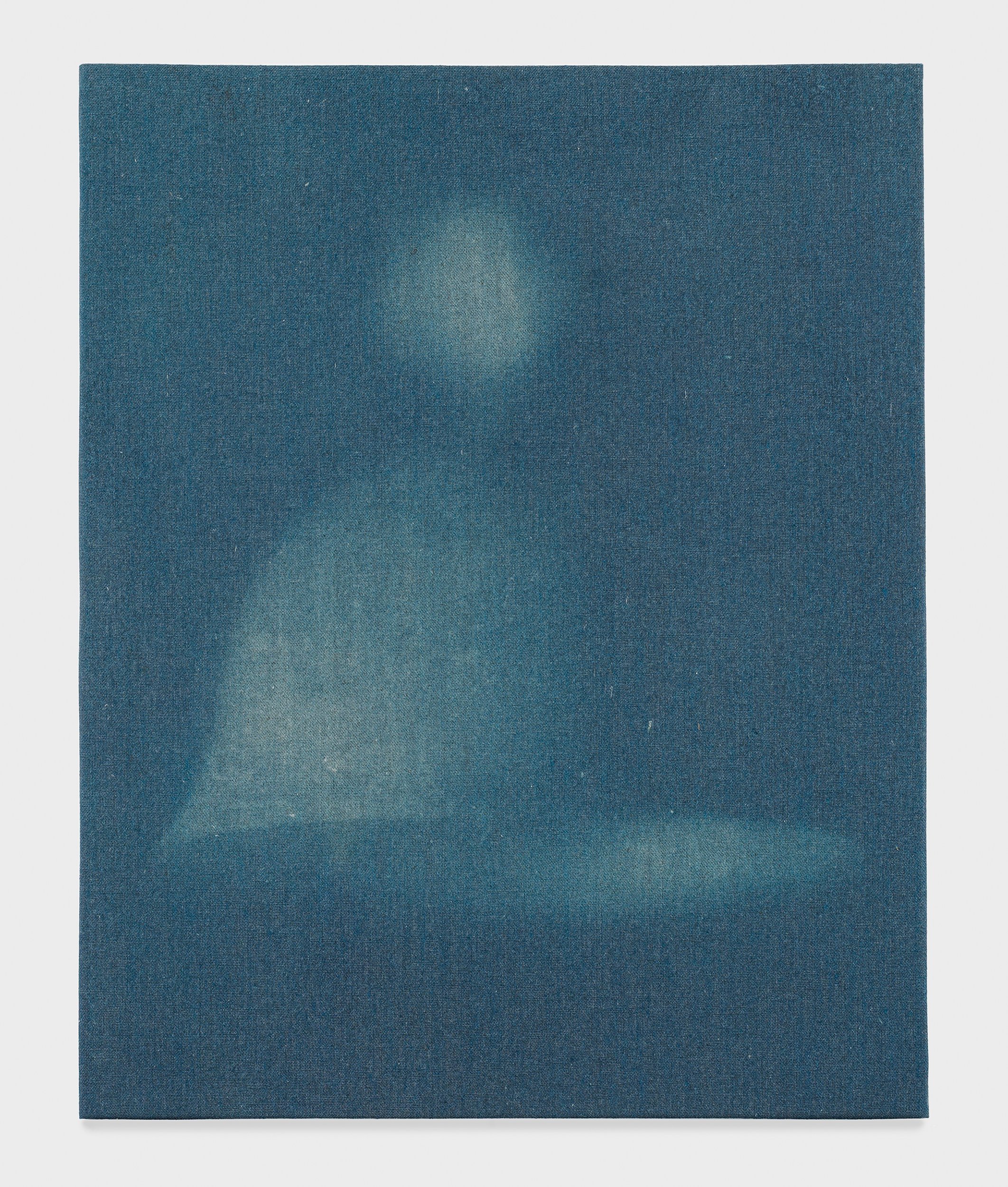

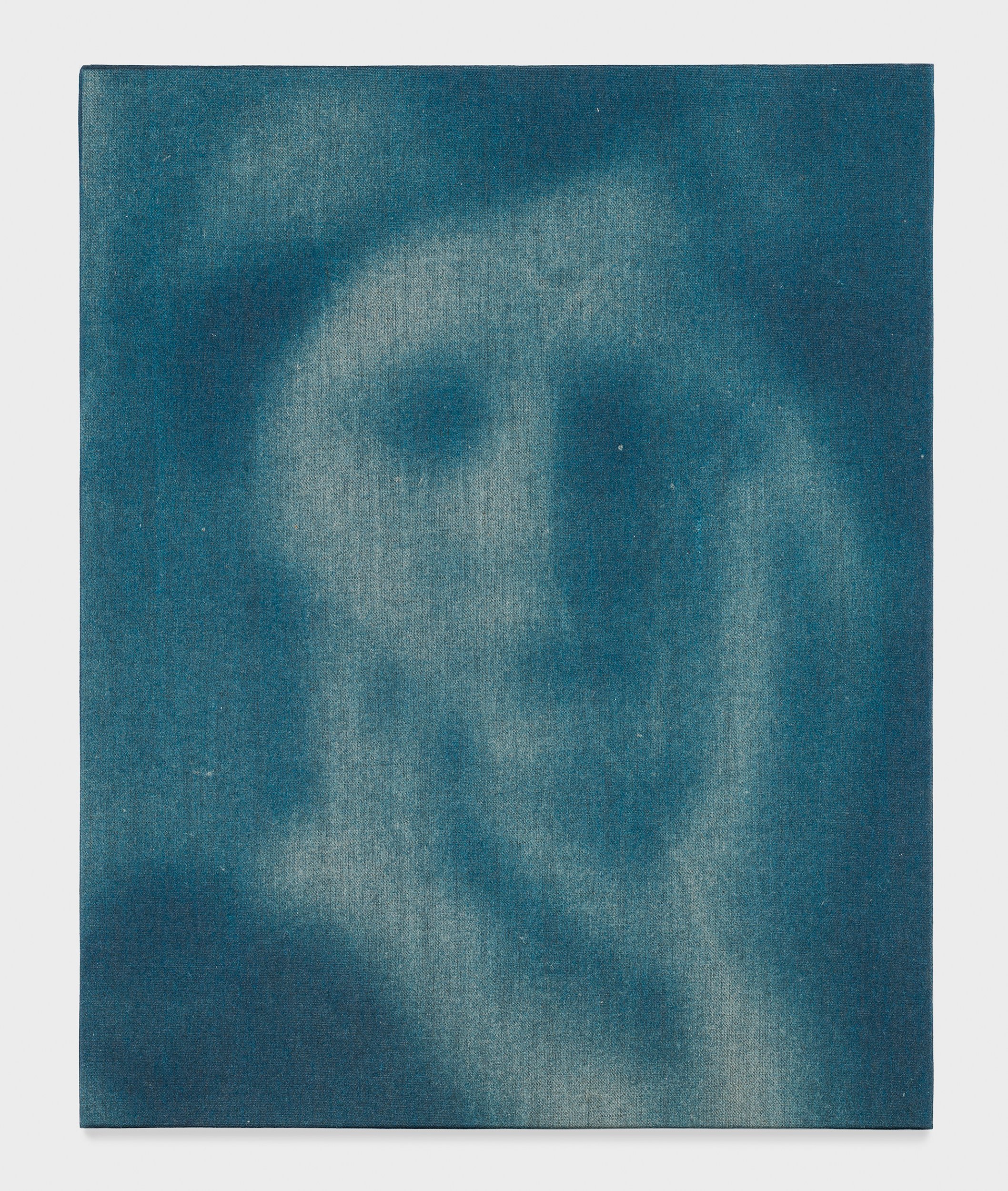

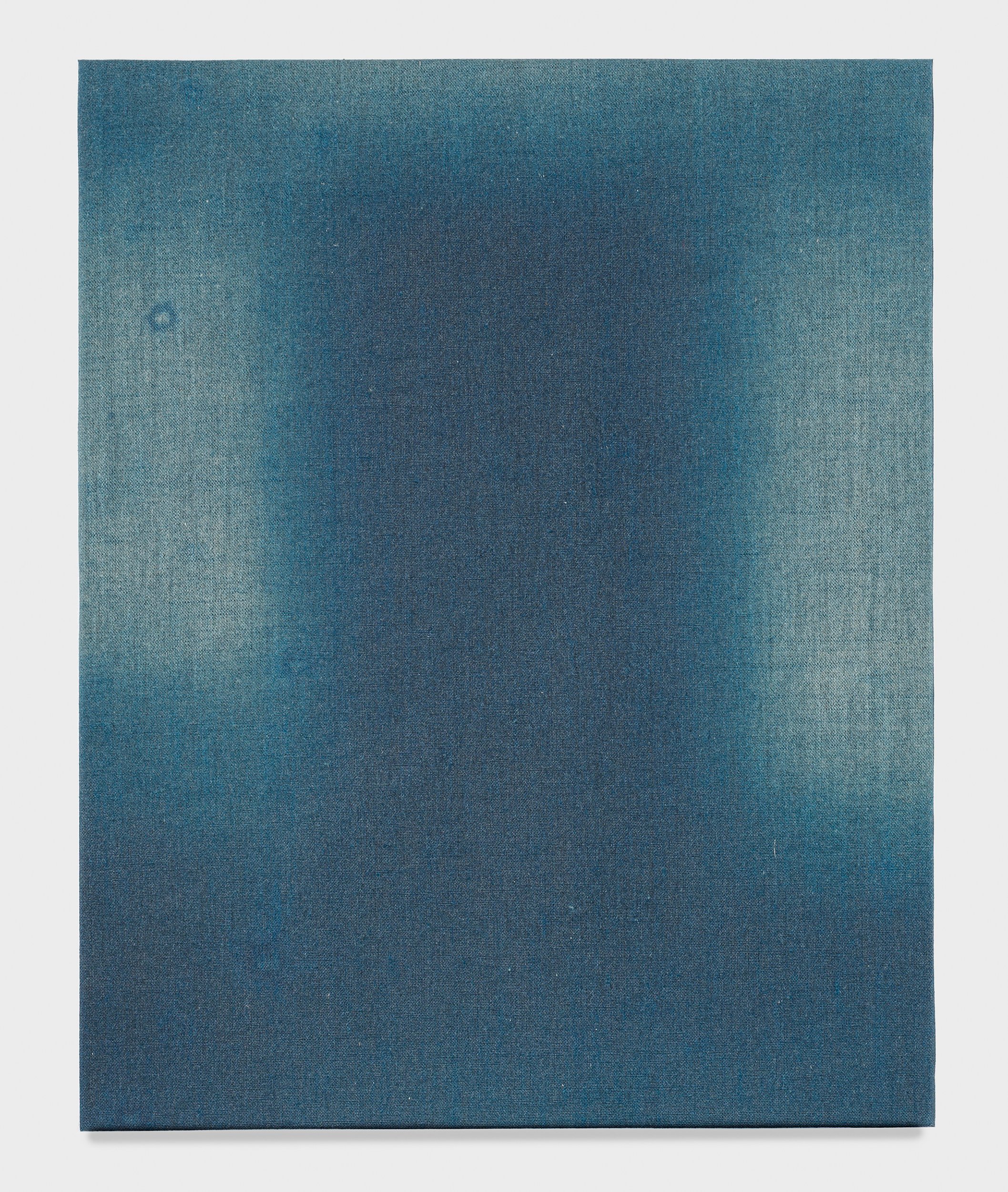

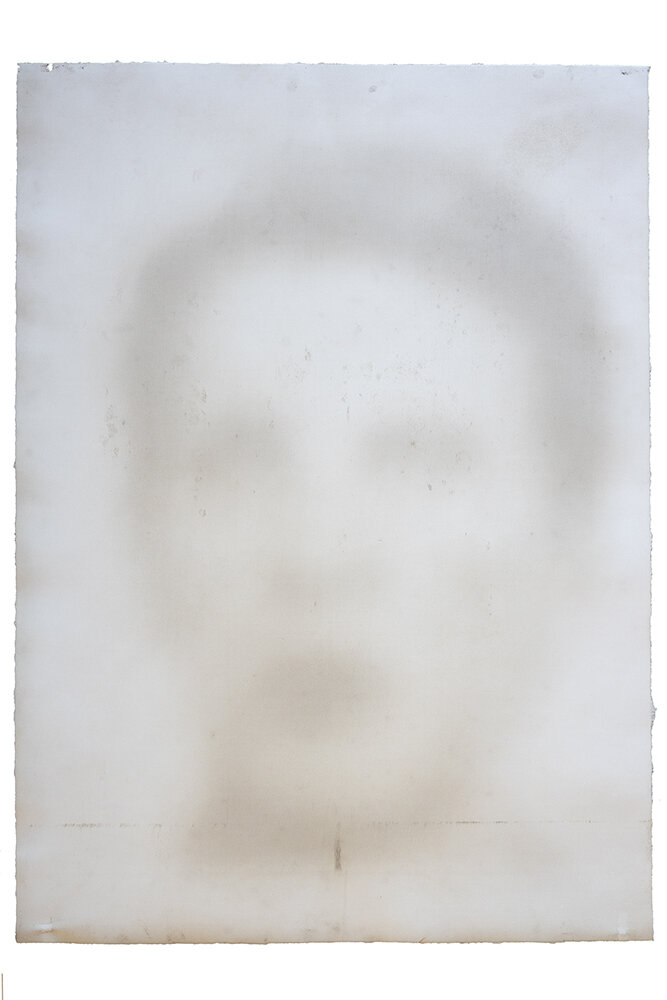

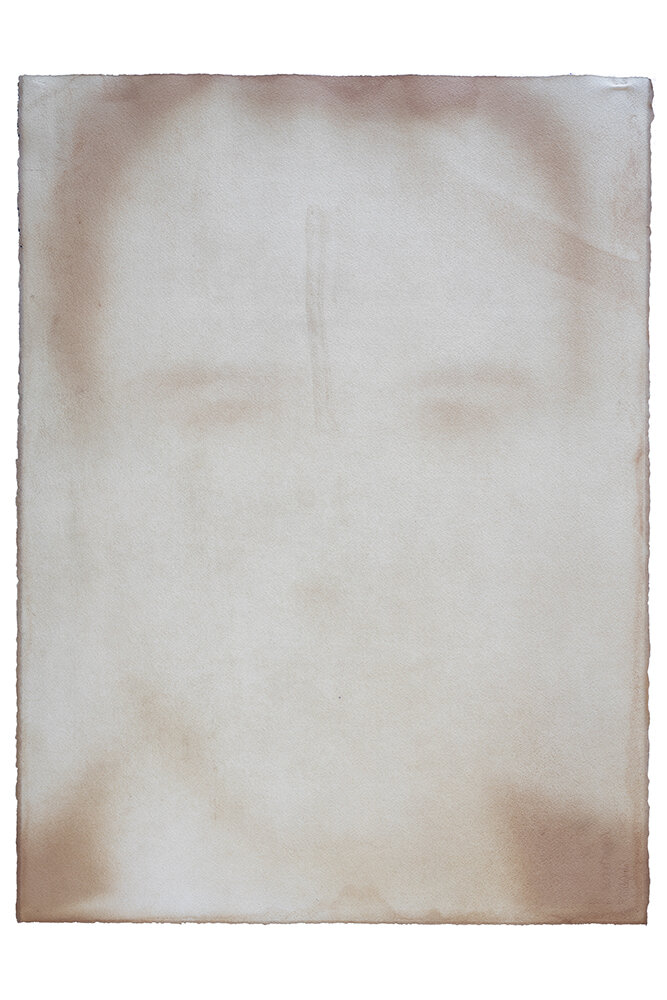

The rich blue tones of these photographs come from the cyanotype process. Originally a camera-less technique also known as a sun print, this process was born in the 1840s from the scientific experiments of Sir John Herschel (1792–1871). The brilliant blue colour typical of a cyanotype derives from the iron salts present in the emulsion, emphasising the process as the oldest non-silver photographic printing technique. Photography is inherently connected to notions of materiality and reproducibility, which relate closely to ideas of experience and collectiveness. These elements are intertwined, yet independent; likewise, each image in The Pond is similar, yet unique. The cyanotype process is, in many ways, the embodiment of these paradoxes, at once a negative, a positive and a blueprint, simultaneously deeply material, reproducible and unique. For this body of work, Jeppesen made these cyanotypes on a linen, rather than a paper, base. By nature, cyanotypes are unique, a singular representation of an image rendered by the sun’s rays; however, Jeppesen also employed negatives in his method, acting as a stencil around which the sun wrought. After coating the linen cloth with sensitising chemicals, he exposed it for between five and ten minutes in direct sunlight with a negative laid on the cloth. The sun penetrated and exposed all of the places it could reach, turning the lightest areas of the register into the deepest blues in the final positive image. The places that appeared dark in the negative were protected from the sun’s searching rays, remaining pale and ghostly in the result. The melding of historic and modern printing processes epitomises Jeppesen’s implementation of photography in this project; it seeks representation, not record, and the experience of discovery and relatability in the representation of something recognisable.

Jeppesen has examined materiality throughout his career, and has become known for his experimentation with pins, folds and other physical additions to the photographic print. Increasingly, Jeppesen has striven to relinquish elements of the process that afford maximal control, instead introducing obstacles that increase the role of chance. The delicacy of paper contributes to the precision of photography; it must be carefully prepared, developed and rinsed. In the cyanotype process, water is a key component of the latter steps, as the image emerges while being washed. Jeppesen discovered that water could also be used to alter the tonal qualities of cyanotypes if immersed for extended periods of time – though extended enough to dissolve any paper’s pulp. Given this, linen provided a rigidity to the base material, allowing for this experimentation of tone. Typically, photographic emulsion holds the image upon the paper’s surface. By printing on linen, the image is embedded into the fabric fibres themselves, bleeding into watery pools of inky blue that travel the fibre channels. So the image is at once emerging and disappearing; an echo, almost, of itself.

The absorbance of the cyanotype’s blue pigment mirrors the manner in which collective identity is shaped and moulded by the absorbance of human experience, and the way that the marshy Danish ponds subsume the detritus of the ecosystem within which they exist. The cyan ripples in Jeppesen’s prints are reminiscent of a pond’s watery texture, pierced by sunlight and weightless, concealing a lifetime’s worth of experience just beneath the surface. In the pond – and in photography – water has a dual capability; it is both cleaning and corrosive, constructive and destructive. It is the source of life and the source of after-life, inherently connected and disconnected from the physical world; similar to how hands are both connected and removed from the body, tools with which to build and destroy that maintain a capacity to be both saviour and villain. The cyanotype process relies upon the essential qualities of photography, light and chemistry, both of which are powerful though not entirely controllable entities, much like the human character. In this way, each image is a destiny in itself, mirroring the fate of humankind.

The themes raised in The Pond are particularly poignant at this moment in social, cultural, political and environmental history, when destinies feel ever more fragile and the power held by human hands is acutely apparent. Increasingly, nationalist trends emerging worldwide place a lens on human nature in relation to conflict, mortality and emotionality; now fervent sources of polarised opinion. Rather than finding solace in commonality, lines of separation have been conjured, within human communities and between the manmade and natural worlds, that contribute to many of the issues pertinent in today’s social and environmental cultures. The feeling of insecurity evoked by the depths of the pond – a trepidation associated with a fear of the unknown – is becoming established as the emotion underpinning newly normalised, antagonistic political rhetoric. Jeppesen’s work references the disquiet of this trajectory and, at the same time, implies the criticality of balance. In The Pond, hands appear disembodied, suspended in water and ambiguous in their intent, both serene and ominous as premonition. They are lifeless yet the symbols of action, both bold and inert, lacking the consciousness of one aware they are being watched.

Jeppesen pays meticulous attention to how his work is presented, which heightens its emotive potential and introduces a performative element to the viewing experience. These are images that give as much as they are given; the longer one lingers, the greater the depths that unfold in the pond’s cloudy waters. In the past, Jeppesen has shown The Pond lit only by natural light falling into the gallery space. Hostage to mother nature’s tempestuous moods, the success of this relies on bodily reactions that adjust vision according to environmental light levels. This emphasises the connection of the work to nature and, indeed, of humans to nature, in its insistence of physical participation. It also provides an experiential journey of submergence and emergence, which emulates the life of the pond Jeppesen depicts. In this, he demonstrates himself as an artist truly engaged with every facet of his practice.

For Jeppesen, there is a resonance between the experiences of human identity and the visual language of their representation, which, for at least the last 180 years, has been informed by photography. Photography seems to be the ideal tool for Jeppesen’s perspective: rooted in reality, but rich with the possibility of narrative; common, yet individual. Over the course of his career, Jeppesen has proven himself as an artist with a complex, rigorous approach, connecting visually diverse bodies of work with clever threads that endow each with a conceptual equivalence. In The Pond, Jeppesen gives voice to the familiar phrase ‘the power is in our hands’, affording the viewer a compelling insight into how much, exactly, is held in the hand.

Catherine Troiano, Curator, Photographs, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Fixing Form: Adam Jeppesen's Tank Series

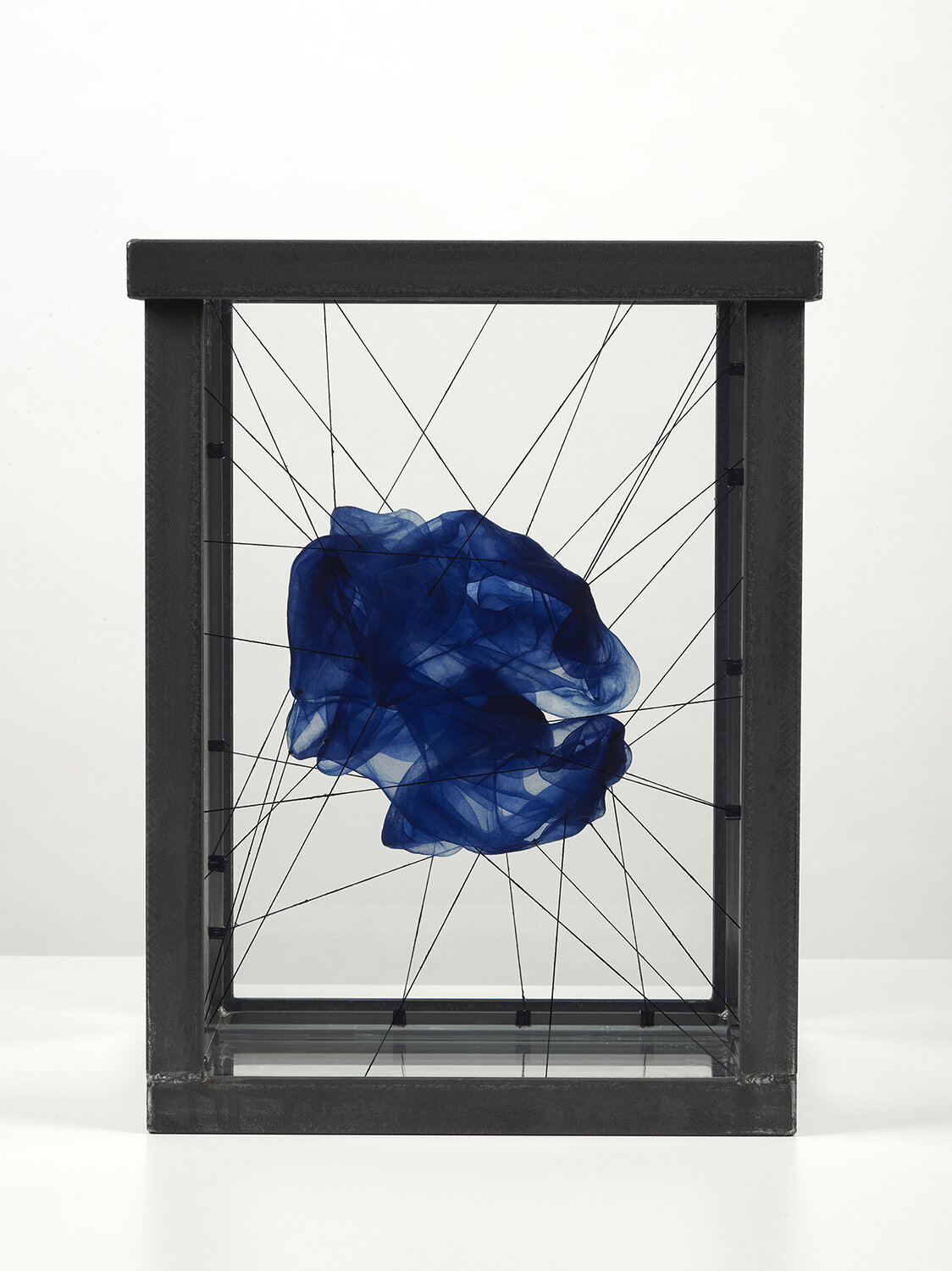

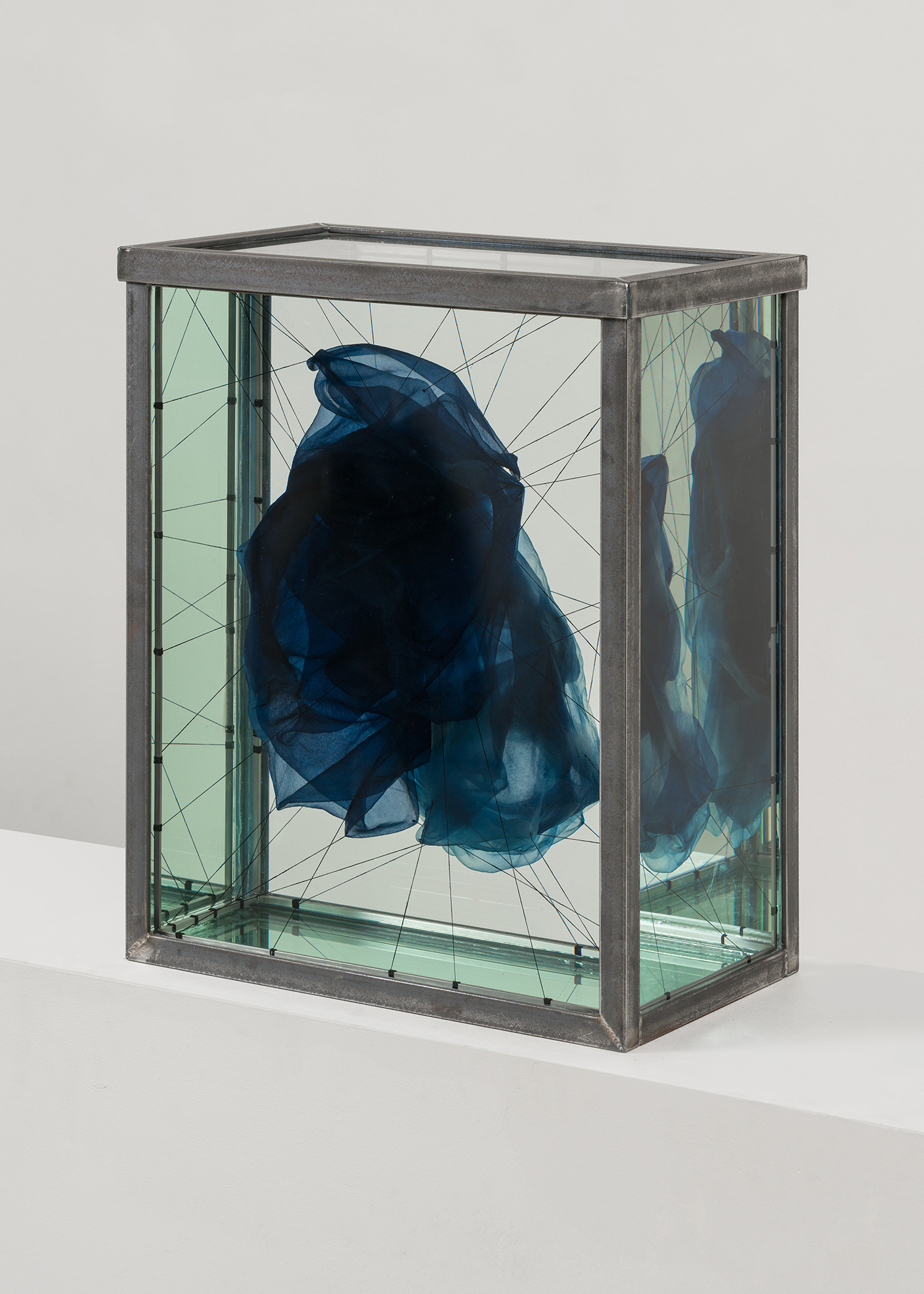

A blue fabric floats inside a steel cage. Immersed in a clear liquid, it glistens yet remains entirely still. The outer edges of the fabric are punctured several times over. Through each puncture hole a black thread has been woven and pulled tight, anchoring the fabric within its metal confines.

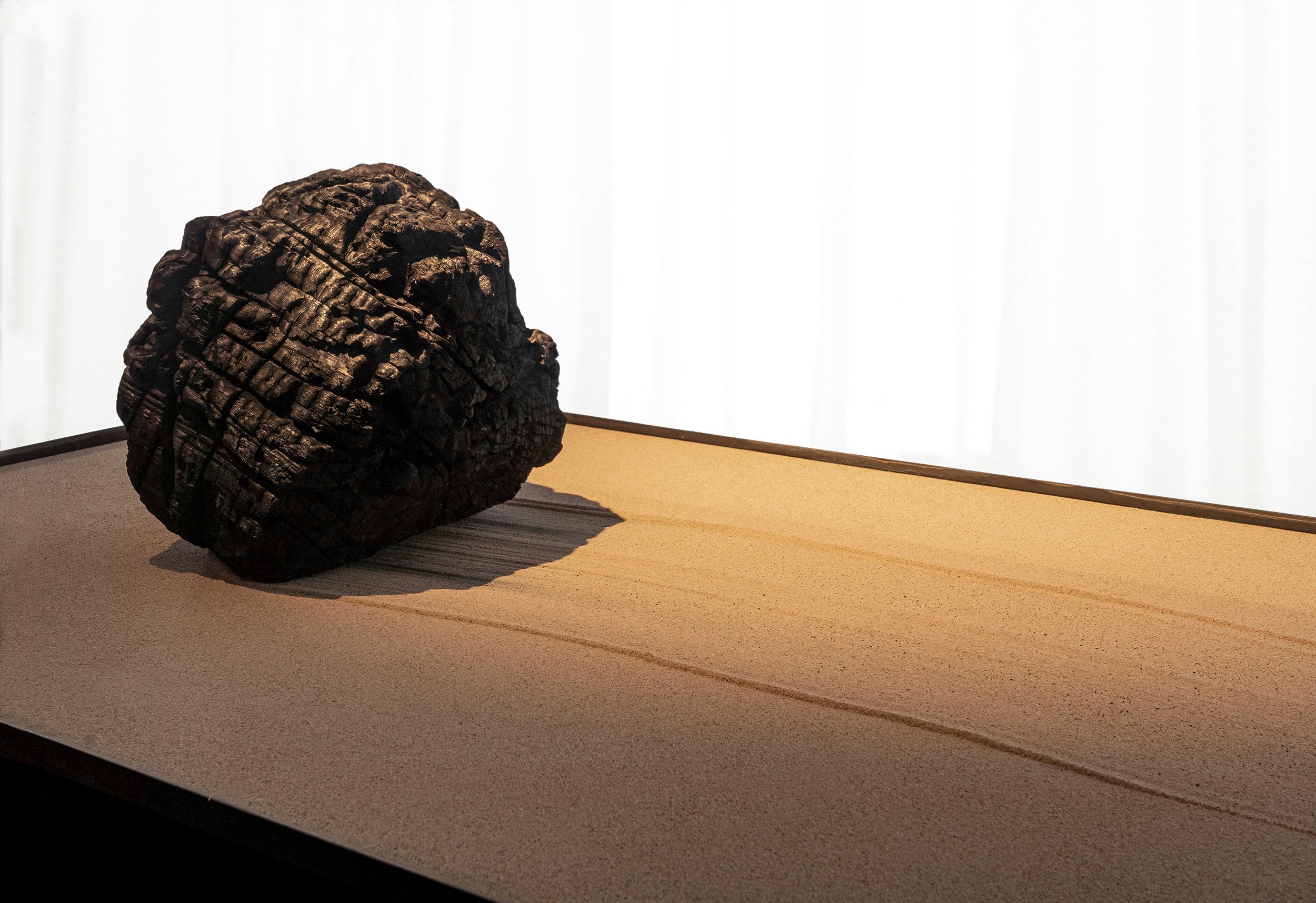

For The Tanks (2016 – present), his most recent body of work, Adam Jeppesen has suspended cyanotype printed fabric in oil-filled tanks. Much of the artist's practice has worked at the edges of photography, pulling at its seams, pushing the limits of what can be considered a photograph. For him, photography has never been the goal but a means to an end. That has never been more apparent than in this body of work, which, although photographic in its origins, makes a decisive pivot towards the sculptural.

The project is a natural progression from the series that preceded it, The Pond (2016 – present). This series of cyanotypes was inspired by observing nature, in particular the processes of decay in ponds. The images depict the artist's own hand, the medium's characteristic blue giving the impression that the hand is floating in water.

Given that nature was the point of departure for both series, it is wholly fitting that Jeppesen has embraced cyanotype. At the dawn of photography, it was the cyanotype that British photographer Anna Atkins adopted for her study of plant life. For The Tanks, the cyanotype is printed on cotton, a material chosen for its robust nature and therefore its ability to withstand the artist's process-driven technique. The cotton is coated in photosensitive emulsion and then exposed to sunlight. The process does not use a camera, reducing photography to its essential and most simplistic elements – material, photosensitive emulsion and light – reminding us that ‘the main instrument of the photographic process is not the camera but the photosensitive layer’.2

By focusing on photographic process and materiality to create an abstract piece, Jeppesen's work has many precedents. The early twentieth century saw many artists parsing the photographic medium into its constituent elements and manipulating them to abstract ends. Chemigrams were made in broad daylight by manipulating photographic chemicals on light-sensitive paper, using wax, polish and varnish to stop chemical reactions. For photograms, it was sometimes simply light itself that was directed onto the paper, manipulated and blocked through masks and filters. For Jeppesen, the quantity of light reaching the surface of the cotton is manipulated by keeping parts of the fabric in shade while exposing other sections to light more directly. Water is often sprayed on the surface to dilute the reaction. The material is then washed and left to dry.

For the early practitioners experimenting with the possibilities of camera-less photography, the creative process often ended when the image was fixed. Although the finished piece may have evoked three dimensions, their physical form was often flat. For Jeppesen, the two-dimensional cyanotype is just the first step in a much longer artistic process that moves towards the sculptural.

Once the cotton is dry, it is subjected to a meticulous process of repeated puncturing. Through each hole, the artist gently feeds black thread. This is done between fifty and three hundred times, depending on the particular piece. It is a process that is linked to dexterity, the careful calculations in pressure and positioning that hinge on the judgments of the artist's hand. Again, we find a visual link to The Pond, the image of the artist's hand floating to the surface of the viewer's mind as if emerging from the murky recesses of a pond.

This process of threading embraces both control and chance. There is no predetermined form that the work should take. The puncture marks are not mapped out in advance and they don't follow a pattern or logic. Their creation is intuitive and responsive, embracing the unforeseen. Yet control plays an equal role, as the needle's action is decisive and absolute. Once a hole is made it is not revised; the creative process always flows forward in time. This intuitive approach extends to the moment that the material is stretched in various directions and anchored to create an abstract form within the confines of the steel case. When the oil is slowly added, whatever form the fabric takes in that moment is embraced.

The teachings of of wabi-sabi, the traditional Japanese philosophy associated with Zen Buddhism, are a key inspiration for Adam Jeppesen. Wabi-sabi is notoriously difficult to define but Leonard Koren, author of one of the foundational texts on the subject, has defined it as ‘a comprehensive aesthetic system, its world view, or universe is self-referential. It provides an integrated approach to the ultimate nature of existence (metaphysics), sacred knowledge (spirituality), emotional well-being (state of mind), behaviours (morality) and the look and feel of things (materiality).’3 The entirety of Jeppesen's creative process echoes one of wabi-sabi’s central beliefs: the acceptance of imperfection and the recognition of the beauty found within it.

Stretched to fit the geometric shape of the tank, the cyanotype is wrested from any relationship to flat abstraction. The wetness of the fabric lends a three-dimensionality to its tones and textures. It invites the viewer to move around it, to experience it from different angles, the body entering into a relationship with the work itself. The directional pull of the thread creates multiple folds in the material. Light flows through it, illuminating some areas whilst unable to penetrate others. This contrast between transparency and opacity, where light illuminates and where it is obscured, gives each work its unique character. It is therefore light — the intrinsic ingredient of photography itself — that bookends the artistic process. Light initiates the creative process when the sun's rays hit the cotton material, then re-inserts itself at a later stage when it spills through the material's various folds, realising the work's final form.

Familiar shapes seem to emerge when one looks at the work, such is the mind's urge to find recognisable forms in abstract shapes. A dancing figure, a bobbing seahorse, a pointing finger, a nebula. There is much joy in this process, which gives free reign to the imagination. It is like watching the clouds morph and re-morph overhead. These shapes are all determined by the directional pull of the thread, however, a pull that seems to interject violently in this playful game of free association.

The process of tying and binding is also violent. It restricts the fabric, pinning it like a butterfly beneath glass. When bound and tied, the splayed cloth could evoke the hide of an animal, strung up and stretched for tanning. The many knots that bind the fabric force it to accommodate an unfamiliar frame, generating a feeling of claustrophobia and panic. There is a sense of being caught like prey in a spider's web, unable to move, frozen. Yet, simultaneously, the submerged fabric appears to float weightlessly, buoyed by the oil that surrounds it. It is peaceful and tranquil. And so, the work might begin to engender less violent connotations; the tangle of threads become less a spider’s web, more a dreamcatcher – a talisman giving protection from bad dreams.

And if we cast our minds back once again to the pond, further dualities surface. The pond is at its core a site of decomposition, a still body of water that absorbs things over time. The cotton fabric could emulate a cluster of leaves slowly sinking into the pond’s depths, moving further through the stages of decomposition with each passing day. Yet the oil acts to intervene in this process, to preserve. The work then seems suspended, held by the opposing forces of preservation and degradation. Cast in this light, the tank begins to resemble a container for experiments, in which some unknown element is preserved for study.

It is between these polarities and contradictions – restriction and weightlessness, violence and tranquillity, degradation and preservation – that the work exists. This notion of preservation is, of course, tinged with melancholy. For the preservation process can only ever slow down degradation; it cannot stop it. Not even the photograph, which slices a moment and freezes it, can stop the march of time. The Tanks remind us that we cannot resist time, try as we might to preserve or stop it; the fragility and transience of everything is guaranteed. As wabi-sabi teaches us, ‘things are either devolving toward, or evolving from, nothingness’.4

The works are truly abstract, of course, as the cyanotypes do not depict anything. In this way, each is divorced from what many people would immediately identify as a photograph, so conditioned are we to associate photography with the depiction of the world around us, with ‘reality’. Yet, abstraction came as naturally to photography as description. Its history stretches back to the medium's earliest days, both in the vortographs of Alvin Langdon Coburn and in the lesser-known Cubist experiments of Pierre Dubreuil. Many of the artists who decided to bend the rays of light towards abstraction did so in order to give expression to internal emotions. Between 1922 and 1934, Alfred Stieglitz photographed the sky above his Lake George summer home more than a hundred times. He called the series Equivalents, as the photographs were equivalents of his emotions, his ‘inner resonances’. Similar concerns are found in abstract painting. In his seminal text, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Wassily Kandinsky advocated for an art ‘that is beautiful which is produced by the inner need, which springs from the soul’.5

If Jeppesen's containers can be understood as hosts for some experiment, the questions they seek to answer are not based on fact or reason, history or culture, but rather in something more intangible, unspoken, perhaps even spiritual. When photography was first invented its ability to fix a likeness was believed to steal the soul of the sitter. But what might a soul look like if it could find a tangible form, one we could grasp? And if it ever were to reveal itself to us, surely the human urge would be to try and trap it, to fix it before it evaporated into the ether? To pin it down, to preserve and examine it, for as long as we could – like an experiment in a test-tube, like a form in a tank.

For Jeppesen, creating this body of work was the product of an inward-looking exercise. One of the meanings of wabi-sabi is ‘to look inward’. It is this same process of looking inward that Jeppesen hopes the viewer experiences on encountering the work. Where that process leads is entirely individual, as no meanings are ascribed to the work. In this way the series retains a sense of incompleteness and unknowability inherent to wabi-sabi. We are invited to be in solitude with each piece, as the artist was in solitude during the process of its making. The work asks the viewer to slow down the process of looking, to approach it in a meditative way. It may be through taking this approach that we can channel one of the core beliefs of wabi-sabi – to transcend conventional ways of looking at things and thinking about existence.

by Sarah Allen, curator of Photography, Tate Modern

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////

TANKS

Adam Jeppesen – New Works

But then hands are a complicated organism,

a delta in which life from the most distant sources

flows together, surging into the great current of action.[1]

Rainer Maria Rilke

Adam Jeppesen's work is characteristically observational and process-oriented, regardless of theme, media, and material. In recent years, the artist has primarily worked with an old photo-processing method, cyanotype.

A technique where colors and designs are generated in the fabric with the help of sunlight, and washed out with the help of water, seems perfect for an artist like Adam Jeppesen. One senses clearly a meditative dwelling upon the material and processes over time, which is characteristic of this artist’s work.

Jeppesen takes an interest in the processes and ever changing conditions of his surroundings. The universe is in constant motion, headed towards or away from its potential, and there is no basis for believing that anything is finished, defined, or complete.

Subject and object are for Jeppesen closely entwined, and the artist’s latest work hints at a reinforced interest in breaking the boundary between space, object and observer. He is fixated on the light and the shadows in the rooms where his pieces are displayed. For him the sphere outside the work itself is not a void, but a world of possibility: the possibility for something to happen, and be experienced. The possibility for an expanded potential of the viewer’s perception and understanding.

But it is not the role of the artist to tell us where to look, or what to perceive. Simply to open up his work enough to create an awareness that brings to life our own internalized experiences.

The artist’s work has been a gradual transition from the two-dimensional, photography-based work towards a more sculptural expression. That shift is now complete, manifested in oil filled glass tanks, wherein a cloth suspended by strings appears simultaneously restrained and free-floating.

It is about the contrast between the sharp retention and stretch of the fabric and the light, fluid weightlessness of the liquid. A contrast and suspense that we also know from Jeppesen’s paper works, fastened with countless pins.

The colorless liquid preserves the fabric in the tanks and enables us to observe the room through the artwork as we move about it. However, upon looking deeper into the glass, we notice that the fluid also distorts the image and prevents us from seeing the fabric as it truly is. The liquid adds an indistinct presence to each piece: an added dimension that, because of it’s complete transparency, is largely experienced as a feeling.

The hands and their many postures are a recurring theme in the framed cyanotypes, offering a strong and immediate glimpse into art history. Not least comes to mind the French sculptor Auguste Rodin, for whom hands as a theme remained a continuous passion, as his extensive studies and collection of antique hands demonstrate. For Rodin, each part of the human body – and hands in particular – were every bit as expressive individually as they were collectively. Of this, his close friend the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote the following: “The artist’s task consists of making one thing of many, and a world from the smallest part of a thing. Hands have stories; they even have their own culture and their own particular beauty. We grant them the right to have their own development, their own wishes, feelings, moods, and occupations.”[2]

Hands are significant in our understanding of ourselves as human beings. We can see our own hands without having to look in the mirror. We act, react, shield ourselves and gesticulate towards and against our surroundings with our hands. Therefore, they can, as Rilke suggests, be understood as a world in and of themselves.

But in Jeppesen’s pictures, the hands are disconnected from the body and its experience. They exist without purpose or consciousness and appear to glide weightlessly under the surface, like the fabric within the tanks. That which can be perceived as a familiar gesture, is just an empty and arbitrary echo from a lifeless hand. There exists an inherent melancholy, emphasized by the artwork’s washed out, blue hues. But at the same time, there is also something reconciliatory about the immediate familiarity of the theme, combined with the softness of the cloth’s appearance.

Perhaps therein lie both a reassurance and a proposition, that we must find a larger perspective – also when we deal with the smaller pieces of the whole. That we should pay attention to our presence and experience ourselves as a part of that which surrounds us. With that foundation, perhaps we can achieve greater insight and move in new directions.

Bolette Skibild, MA in Cultural Studies

Translation: Marta Stenz

[1] Rainer Maria Rilke: August Rodin. 2. Edition, 2012. Parkstone International p. 50

[2] Rainer Maria Rilke: August Rodin. 2. Edition, 2012. Parkstone International p. 50

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////

TRACES OF A JOURNEY

BY ANN-CHRISTIN BERTRAND

“Nothing that exists is without aw.”

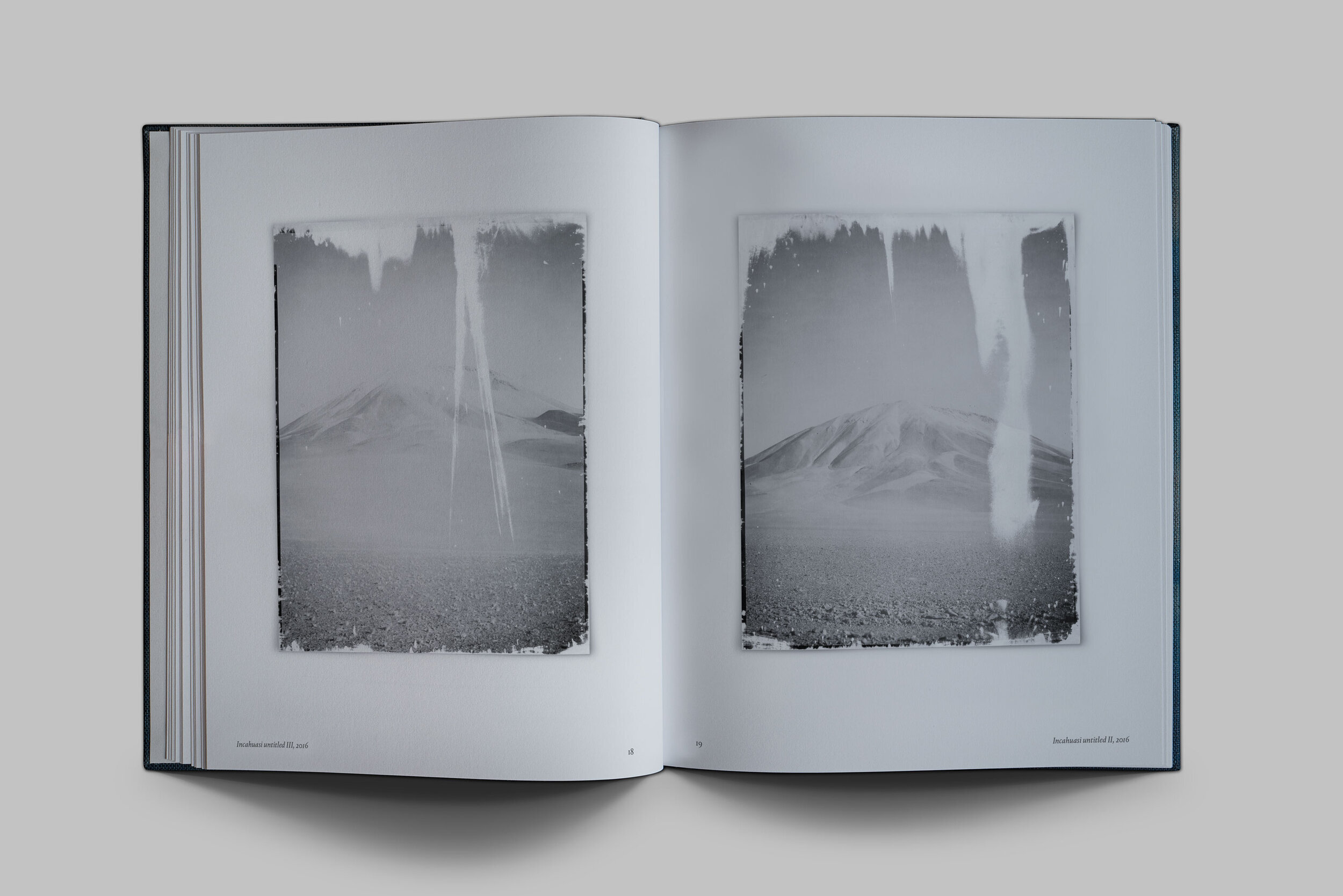

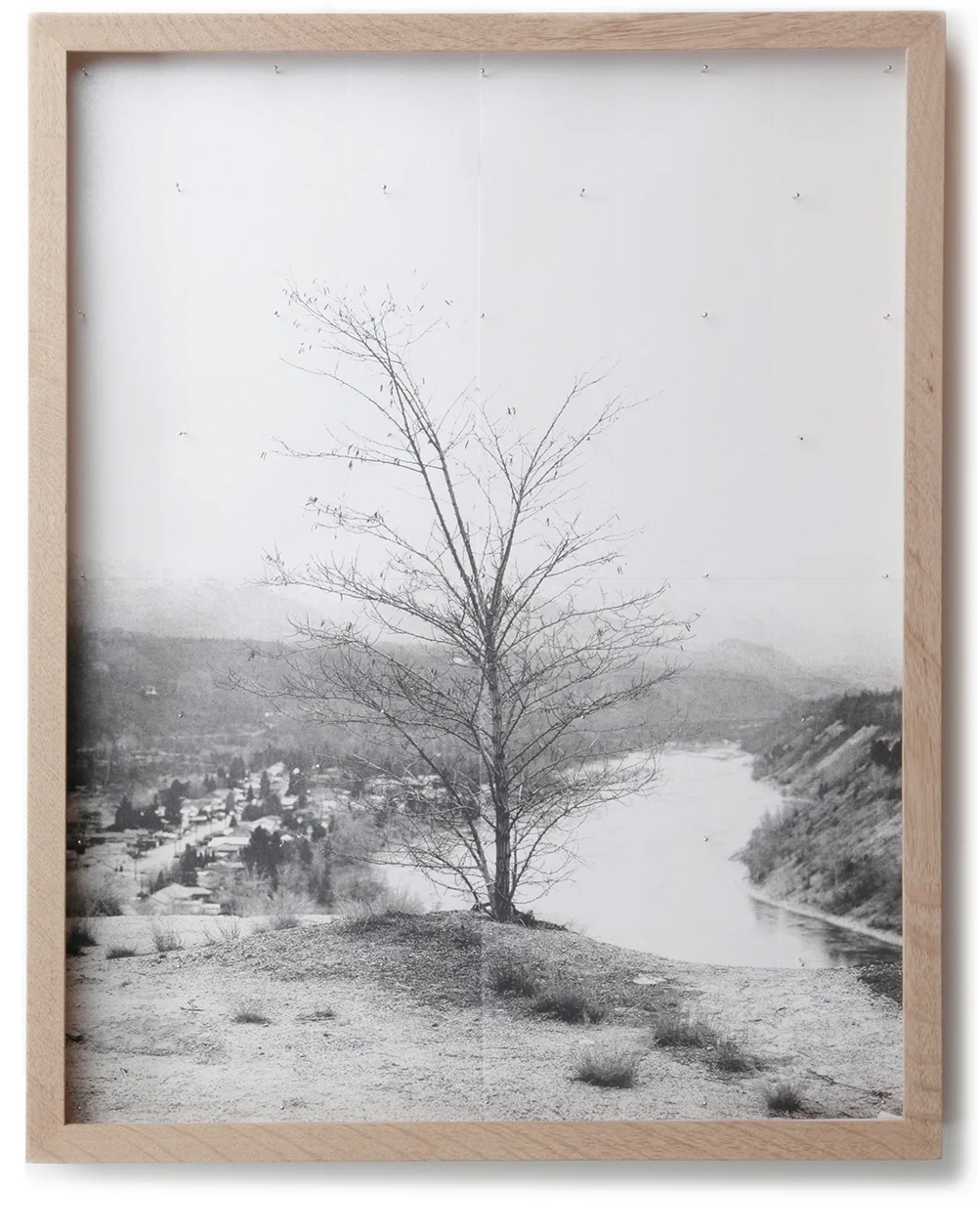

Encompassing multiple series, Adam Jeppesen’s project flatland camps Pro- ject evolved during a 487-day journey

by the Danish artist from the Arctic to the Antarctic. The works he photographed along this route are witnesses to a quiet dialogue between the artist and the landscape surrounding him. At the same time, they also tell of the physi- cal voyage of his photographs. When the lms were changed, speckles of dust and rays of light settled on the negatives, leaving behind scratches, streaks and ecks of light – ‘mistakes’ that alter the surface of the negative but whose signs of wear also chronicle a complete- ly different facet of the photographed landscape. Thus they become an indicator of the natural process and an important part of the recounted story. That is why Adam Jeppesen takes up precisely these ‘mistakes’ and elevates them as both a creative element and a physical testi- mony to his journey, and has since been consciously developing them further

by constantly experimenting with his photographic material.

MATERIALITY

In his series folded, begun in 2014, thin wrinkles snake across the images of imposing mountaintops and snow-covered glaciers. Printed on rice paper, the landscapes are folded in regular inter- vals by the artist so that a ne network of A4-sized sequences covers the under- lying landscapes. The rice paper is so delicate that the surface of the pa-

per and the color pigments do not break when folded, but are preserved. Because of this, the print does not appear de-

stroyed but instead is reminiscent of a folded poster or map. At the same time, the thin, fragile rice paper stands in intriguing contrast to the monumental- ity of the glaciers and mountain peaks. The mighty folds of our earth’s surface, shaped over millions of years, collide with a type of paper that is more gener- ally associated with a breezy lightness, fragility and transience.

SPATIALIZATION

folds: they organize the surfaces in space and offer our eyes a delicate structure along whose barely visible lines we can direct our gaze. Instead

of losing themselves in the expanse of photographic surface, the folds give us an anchor and enable a deeper percep- tion of every little detail of what is depicted. They also illustrate the tran- sition from two-dimensional surface to three-dimensional shape. Through this folding technique, Adam Jeppesen adds a performative and sculptural aspect to his prints – here, photography is un- derstood much more as an object than as a at print. The resulting relief-like elements act like a lter between us and the depicted images and thus allow for multiple levels of perception. Visual and spatial representation overlap and allow us to become aware not only of the content but also of the material and surface of the photographic print.

THE PuRE, THE PERfEcT AND

THE BROKEN PART Of IT

This is an approach that not only informs the folded series, but also ear- lier works from the flatland camps Pro- ject. Throughout these works, the artist explores the aesthetic value

of imperfection, the search for a balance between purity, perfection and the damage they contain – and hence the physical traces and imprints that

we leave behind and can barely control. The studio is just as important to this process as the journey itself. This is where the subsequent artistic interven- tions into printing procedures, material and presentation style turn the photo- graphs into artworks that cannot be seen in isolation from this unique production process. Photography as physical process – the reproducible medium becomes an artistic object and a unique piece.

In the series Xcopy (2011-2012), Adam Jeppesen dissects his images into man- ageable A4-size formats, then copies them and, using ne needles, nally reassembles them back into the origi- nal motif. In Ghosts (2013-2014), on the other hand, he modi es the traditional printing technique of photogravure so that the printing plate is not coated with ink before every printing, but only once to begin with. The resulting images fade ghostlike from sheet to sheet, un- til only a white surface remains in the end. The work deliberately questions the concept of a ‘perfect’ image, which is revealed to be a very subjective and in- dividual choice depending on the observ- er. Adam Jeppesen’s objects are always framed, thus showing that the artistic experiment within the production process is to be understood as a substantial part of the nal artwork. At the same time, the frame signals that the experi- ment has been concluded, that the artist has de ned precisely this form of ap- pearance and presentation as complete.

TEMPORALITY

Other than in conventional photography, the works in the flatland camps Project also illustrate different levels of temporality. In addition to the tempo- rality of photography, which attempts to capture a speci c moment in time, it is precisely the subsequent artistic pro- cess that in this case not only creates a sensitivity towards the photographic material, but also for the perception of time. After all, the artist’s subsequent interventions, his work on the mate- rial, visualizes not only the physical but also temporal traces – the passing of time is made physically palpable and manifest.

THINKING ABOuT PHOTOGRAPHY

In this sense, flatland camps Project

is not only a journey that began in 2009 and has provided Adam Jeppesen with material for numerous artistic series until today, but above all it also represents a very deliberate re ection on the medium of photography. Whether it is the photographic surface, material- ity, temporality, outward appearance or printing process – Jeppesen uses these aspects as a starting point for his artistic work, and analyzes their nature and questions their function and percep- tion. With this approach, he typi es a tendency in contemporary art that has reacted deliberately to deeper changes within photography since the introduc- tion of digitalization, a tendency that seeks – precisely through an explora- tion of the medium, its characteristics and materiality – to playfully analyze, expand and rede ne its conception and boundaries.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////

Adam Jeppesen, Martin Asbaek Gallery, Copenhagen, 21 September – 21 October

By Martin Herbert, ArtReview, September 2017 edition

Clearly not a party person, Adam Jeppesen has over the past decade spun large-scale photographic projects from his activities as a roaming solitary. The Danish-born, Copenhagen- and Buenos Aires-based artist’s calling card series/ book, Wake(2008), was assembled ‘in the secluded backwoods of Finland’ from photos made during seven years of nomadic wandering – resolutely minor-key images including overcast landscapes, spectral power lines, flickering shadows on old interiors – and merged a German objective documentary approach with something more impressionistic, mood-driven. A later series, Flatlands (2015), documents a 487 day journey from the Arctic to the Antarctic, down through North and South America, leaving society behind in the process and once again mixing the urge to document – to prove what he did, even – with a subjective overlay. Here, Jeppesen allowed his negatives to get scratched, and manipulated the ensuing prints in various ways, from linking multiple sheets to sticking starry constellations of pins in them. In his latest series, The Pond (2017), the landscape that was maybe always a cipher for an interior world has disappeared, though Jeppesen’s attention to analogue photography persists. He’s been making cyanotypes, on linen, of hands, gesturing obliquely but intently – images that feel, technically, like they could have emerged from any moment in photography’s continuum, their subjects freefloating in time.

////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Cyanblå udstilling overrasker med gennemført æstetisk objektkunst

Et sted mellem drøm og dokumentation: Adam Jeppesen overrasker en del på sin seneste udstilling. For nu laver fotografen også objektkunst.

Af Peter Michael Hornung, Politiken 2 Oktober 2017

Endelig en ny udstilling med Adam Jeppesen!

Men denne gang ingen majestætiske og mystisk manende fotos af sneklædte bjerge eller af øde, udtørrede, størknede vidder! Og ingen fine lige folder i de billeder, der hænger på væggene!

Kan det være den samme kunstner, som fotoentusiaster husker så godt fra hans ambitiøse ’The Flatlands Camp Project’, hvor han – kun med kameraet som selskab – rejste fra Arktis over Nord- og Sydamerika til Antarktis?

Ja, det er den samme Adam Jeppesen. Men kan man se på hans nye værker, at han har fået sin uddannelse på Danmarks fotografiske billedkunstskole, Fatamorgana, eller at han i dag bor og arbejder i Argentina?

Nej, det er ikke bestemte genrer eller teknikker, han demonstrerer, eller bestemte lokaliteter, han vil vise os med sine billeder. Det er i stedet denne gang noget helt andet: en hånd eller nogle håndstillinger, som ifølge kunstneren er overført fra negativer til stykker af linned ved hjælp af en teknik fra fotografiets absolutte barndom: cyanotypien.

Den blå farve, som gør hænderne – og nogle foldekast – synlige og giver dem form, går også igen i det fine stof, der er lukket inde i udstillingens transparente objekter.

Stoffet, som synes let som silke, er anbragt i akvarielignende beholdere af forskellig størrelse, hvoraf nogle står på gulvet, og andre hænger på væggen. Her er stoffet spændt ud med tråde fra alle sider. Det synes at svæve vægtløst, men uden at røre sig i den væske, som beholderen er fyldt med til randen, og som vi ikke kan se, kun mærke.

Som tidligere i Adam Jeppesens fotografier søger han måder, hvorpå han bedre kan dokumentere det stof, som drømme er gjort af. Hvis han overhovedet kan dokumentere noget, er dette ’noget’ forestillinger, ikke iagttagelser.

Han vil vise os, at selv om et værk i sig selv er meget nærværende, kan det godt fortælle om noget, som reelt er fraværende. Men det kræver et fotografi, som balancerer hårfint mellem drøm og dokumentation uden at falde til nogen af siderne.

Som der står i den tekst, der gør udstillingen følgeskab: »Det er ikke altid vores ærinde at kunne forklare alting men netop at lade vores visuelle sanser guide os og måske lede os til forståelse«.

Apropos Adam Jeppesens billeder – også i denne forbindelse – er forståelse, det at kunne forstå, ikke ensbetydende med det at kunne gennemskue.

Vi skal ikke gennemskue den natur, eller de udsnit af den, som Jeppesen viser os og iscenesætter for os med sine billeder og objekter. At trænge ind i noget er også at gennemskue det. Og når man først kan gennemskue denne natur, så bliver den triviel. Og så forbløder den og trækker vores fantasis forestillinger med sig ned i ligegyldigheden.

Vi har ikke brug for at afmontere den forundring og gådefuldhed, som kan være den indirekte konsekvens af dette møde.

Vi har endnu ikke nævnt det, som springer mest i øjnene på udstillingen, nemlig det gennemført æstetiske i hele opstillingen, og hertil bidrager især den blå tone, som er den koloristiske overskrift over det hele. Umiddelbart burde denne æstetiske indpakning trække ned. For er det hele ikke meget lækkert? Og for lækkert?

Men Adam Jeppesen – som tidligere var fotograf eller kunstner med fotografiet som medie – bør belønnes og opmuntres for sin uforudsigelighed, for sit mod til at turde gå andre veje.

Efter en udstilling som denne er det, som om han har føjet noget nyt til det, man troede man vidste om ham. Som kunstner rummer han flere muligheder, eller kald det ambitioner eller visioner, som man stadig har til gode at se udfoldet.

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Beneath the surface

For Adam Jeppesen there is no “either/or”. Things simply are. For better or worse.

In recent years, Jeppesen has been exploring various materials and printing techniques, out of a desire to get even deeper into the process and break with the smooth surface of photography. This was seen in his last solo exhibition X at the Van der Mieden Gallery in 2014, where desolate landscapes were translated into a series of photogravures, in which the same motif slowly faded out through the series, in an continuous process towards the full or empty image.

In the current series, ‘The Pond’, the artist has moved completely away from the landscape and has turned his attention to ourselves, which has resulted in a study of hands transferred from negative to linen through the use of cyanotype.

The textile has now replaced the paper, and the images lie more in the direction of painting and the connotations that we associate to painting – not only because of the obvious association of the textile with the canvas and its resulting materiality, but also because of the immediacy of the pieces. In Jeppesen’s works, a movement has long been apparent away from the sober, documentary gaze of photography towards something more allusive or suggestive. We now see a sensibility and tenderness, without distance, that speaks directly to our emotions.

At the same time, there is once again an inherent tension between the way that the imprint reveals the technique, and the imprint as a trace – or perhaps even a kind of mythological evidence: There is something dreamy and puzzling about these pieces – reminiscent of legends like the Shroud of Turin. As in sculptures from antiquity or the Renaissance, the hands in ‘The Pond’ are depicted slightly larger than reality, so that we can better sense the presence and the strength they leave in the imprint.

The blue colour of the cyanotype, together with the series title, ‘The Pond’, underlines the perception that these hands lie beneath the surface. That they are floating in water, in a weightless condition; an apparently gloomy, disturbing image. Hands that are sometimes hard to perceive as such on the basis of our general world of experience. At the same time, however, they also exude an atmosphere of something peaceful, almost conciliatory: The beauty that arises when something has taken place, and we are now heading into another state. This duality is reflected in the water, which is both life-giving and lethal. Cleansing and corrosive. Constructive and destructive. As the hands hover there with no connection to the rest of the body, we understand that everything is a process; a process in which something is built up in order to be broken down again, and thereby enter into a new state. Perhaps it is the artist’s way of telling us that we have to dare, without judgement, to look at everything that lies beneath the surface. Which is not necessarily only dark, but just not recognised or understood. That which simply is.

Bolette Skibild, MA in Cultural Studies

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////

DESIGN BRIDGEN VISITS: ADAM JEPPESEN – OUT OF CAMP AT FOAM PHOTOGRAPHY MUSEUM

This blog post started out as a review of the current Adam Jeppesen exhibition at one of my favourite Amsterdam spaces, Foam Photography Museum. But before I get to that, I want to tell you a story…

Skip back to Edinburgh, 2014, my good friend Craig turns to me at my desk, grasping a faun coloured book, adorned with a monochrome leaf and white italic sans-serif text, Wabi-sabi, for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers. “Mate, you have to read this book!”

I pick up the book. It’s a warm, tactile, uncoated texture — the kind where you really feel the grain — you sense this paper once lived as something else. I flick through the pages; large grey type, interspersed with unusual, yet intriguing black and white abstract photography; scratched tables, leaves pinned under heavy-mud, cracked pottery.

And so I read, “Wabi-sabi is the quintessential Japanese aesthetic. It is the beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It is a beauty of things modest and humble. It is a beauty of things unconventional…”

It wasn’t for another year before I picked up this book again. Now living in Amsterdam, browsing in a bookstore, that warm faun paper smiled at me once more, “Wabi-sabi, Leonard Koren.” Something about this culture was lighting a fire inside me. It went against my schooled instinct. Throughout my career as a graphic designer I have striven for perfection — typesetting, colour, production — everything has to be perfect. And here in this world, imperfection is beauty.

In his book, Koren examines the principles of Wabi-sabi, contrasting it with Western ideals of beauty; where it is perceived slick, seamless, flawless, Wabi-sabi celebrates the coarse and unrefined, the weathered and the aged. It celebrates the transitory, the unfinished — it reflects life itself.

Fast forward to 2017, I find myself in Foam Museum, admiring the work of photographer Adam Jeppesen. Now, Adam Jeppesen isn’t Japanese, he was born in Kalundborg, Denmark in 1978. I don’t even know if he has an active interest in the Japanese aesthetic, but there was something that immediately struck me as I indulged in the Out of Campexhibition at Foam… Wabi-sabi.

The works that make up Out of Camp are a result of Jeppesen’s solitary journey overland from the North Pole to Antarctica in 487 days, and the repeat visits that followed. The photographs bear witness to a strenuous journey, while the images of remote and rugged landscapes are suffused with a sense of serenity and contemplation. “I was particularly interested to explore what being alone does to you. For me, the landscapes reflect this isolated and solitary state of mind.” Jeppesen’s own journey reflects the spiritual values of Wabi-sabi, as detailed by Leonard Koren:

- Truth comes from the observation of nature

- Greatness exists in the inconspicuous and overlooked details

- Beauty can be coaxed out of ugliness

An important aspect of Jeppesen’s work is his labour-intensive approach. He only works with analogue photography, and he spent years organising and printing the negatives. He abandoned his search for the perfect print in favour of cheap reproductive techniques, such as photocopying. Coincidence and imperfections are essential elements in his work. A particular favourite of mine is Jeppesen’s Folded series. Magnificent glaciers are presented printed on rice paper, divided through A4-size grids through subtle folding patterns, as with a map. The delicate texture of the paper contrasts with the indestructible appearance of ancient rock formations. Half-tone patterns can easily be seen in the paper — a clear reference to the nature of the limited printing techniques used.

Wabi-sabi itself looks to “get rid of all that is unnecessary” and “focus on the intrinsic and ignore material hierarchy”. Jeppesen’s images are earthy, irregular and imperfect: it’s what makes them so raw and beautiful.

In Chalten I, damages as a result of physical hardship during the expedition are left un-retouched and remain clearly visible. In a time when the image has become infinitely perfectible and reproducible, Jeppesen experiments with the photography as a unique object that is subject to the forces of change and decay. With damaged edges, and a tarnished surface, this art — like the artist himself — has travelled: eroded maps of an inner-journey.

In the series Scatter, true to Wabi-sabi values, Jeppesen revisited discarded negatives in search for previously overlooked details, damages and coincidences that had previously gone unnoticed. Koren writes, “Wabi-sabi is about the minor and the hidden, the tentative and the ephemeral: things so subtle and evanescent they are invisible to vulgar eyes.”

By carefully dissecting and recycling his own archive, Jeppesen assigns new meaning to otherwise discarded material. The grainy details surpass the original subject of the photograph, to highlight its vulnerability and transience as an object. Comparisons can be made with the Wabi-sabi universe. Leonard Koren writes:

“Things are either devolving toward, or evolving from, nothingness. As dusk approaches in the hinterlands, a traveler ponders shelter for the night. He notices tall rushes growing everywhere, so he bundles an armful together as they stand in the field, and knots them at the top. Presto, a living grass hut. The next morning, before embarking on another day’s journey, he unknots the rushes and presto, the hut-deconstructs, disappears, and becomes a virtually indistinguishable part of the larger field of rushes once again. The original wilderness seems to be restored, but minute traces of the shelter remain. A slight twist or bend in a reed here and there. There is also the memory of the hut in the mind of the traveler — and in the mind of the reader reading this description. Wabi-sabi, in its purest, most idealised form, is precisely about these delicate traces, this faint evidence, at the borders of nothingness. While the universe destructs it also constructs. New things emerge out of nothingness.”

In Adam Jepessen — his work and his personal journey — I truly felt that I encountered a deep expression of the aesthetic and mind-set of Wabi-sabi. To fully appreciate Wabi-sabi is to understand that we too are imperfect; we are flawed, and have imperfections. It’s a lesson to all of us to appreciate the simpler things in life. A lesson to myself as a designer to see beauty in the creative journey and the traces that it leaves. Our ideas for brands are born out of a human process; we think and we sketch, we may collaborate with a craftsman; their marks and these stories live in the final design. Like Adam Jepessen, we too can ignore material hierarchy and burrow deep down to the core; to the subject, and to the idea.

In my exploration of Wabi-sabi I stumbled upon an article by blogger George McHenry. Via George, I end with words far greater than mine. “I am reminded of the lyrics of Leonard Cohen, “Ring the bells that still can ring, forget your perfect offering, there is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.”

Adam Jeppesen – Out of Camp is at Foam Museum Amsterdam until 27 August, details on the Foam website.

BY: Brendan Conn

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Alene i den rå natur med et gammelt kamera

By Erik Jensen, Politiken 17 Juli, 2016

Den danske fotograf Adam Jeppesen viser fotos fra sine lange ensomme rejser på hele to udstillinger i Berlin. Bag ham ligger den lange færd fra Antarktis til Nordpolen i eget selskab.

Endelig var han tilbage i civilisationen efter halvandet år, 487 dage i vildmarken, i selskab blot med sit kamera. Nu skulle han først vænne sig til alle civilisationens indtryk og lugte som for eksempel den hårshampoo, der var lige ved at slå ham ud. Så skulle han se på alle billederne fra turen fra Antarktis til Nordpolen hjemme i København.

Men før han drog af sted, havde Adam Jeppesen skilt sig af med både sin lejlighed og det studie, hvor han normalt arbejdede med sine fotografier. Derfor tog den danske fotograf hurtigt på rejse igen.

»Jeg fik tilbud om at komme op på et refugium i det nordlige Island. Omgivelserne passede mig rigtig godt efter så lang tid med primitivt liv i ensomhed. Men der var ingen tekniske faciliteter til at arbejde med billederne. Der var ingen printer, bare en gammeldags fotokopimaskine. Den måtte jeg så bruge i første omgang«, siger han.

Følgelig kom fotografierne ud som mange dele på A4-ark. Adam Jeppesen hængte dem op med knappenåle på en lige så gammeldags opslagstavle og fik samlet sine billeder, der ofte bestod af 16 fotokopierede papirer.

»Efter et par uger kom jeg til at kigge på opslagstavlen, og pludselig kunne jeg vældig godt lide, hvad jeg så. På en fotokopimaskine kan man lave tre variationer – mørke, lys og noget midtimellem. Det var meget mere ærligt over for oplevelsen i mine billeder, end en teknisk perfekt gengivelse ville være. Den grå tone fra kopimaskinen var bedre, end en ren sort farve ville være. Den gengav stemningen af at være i barsk natur, helt alene, helt ærligt og rigtigt«, siger Adam Jeppesen.

Han står omgivet af sine gråtonede fragmenter af landskaber på Berlins måske bedst kendte udstillingssted for fotografi, C/O Berlin, hvor man fra i dag kan se den danske fotografs udstilling ’Out of Camp’. Og konstatere, at fotografierne i den første af udstillingens tre dele stadig består af fotokopier, der er sat op med nåle og tilsammen danner hele billedet.

Egentlig er Adam Jeppesen dokumentarist. Han er født i Kalundborg i 1978, opvokset i New York og i dag bosiddende uden for Buenos Aires i Argentina. Han rejste som mange kolleger fra krise til konflikt og til krig og dokumenterede ødelæggelser og lidelser med sit kamera. Men efter et ophold i Jenin i Palæstina fik han nok.

»Jeg kunne ikke tage det mere og prøvede at finde en helt anden retning for mit liv. Jeg tog til Grønland og blev fisker. Men det gik ikke. Jeg mistede mig selv uden at fotografere og blev klar over, at jeg måtte tilbage. Men måske på en anden måde«, forklarer han.

På cykel til Sydamerika

I juli 2009 tog Adam Jeppesen af sted til Canada. Han købte en stor bil og satte kursen mod den vestlige side af landet og Antarktis. Men noget gik galt fra begyndelsen.

»Det var enormt dejligt at køre i bilen. Så dejligt, at jeg helt glemte at stoppe og fotografere. Jeg blev i tvivl om hele projektet. De billeder, jeg fik taget, var ikke det, jeg forestillede mig, at dem, der sponsorerede mig – blandt andre Det Nationale Fotomuseum i København – ville have. Jeg havde tidligere fundet en stor tryghed i at tage nærmest perfekte dokumentariske fotos, og nu var det hele mere fragmenteret og dystert. Jeg var tæt på at opgive projektet«, fortæller han.

I stedet opgav han bilen. Den blev solgt i Vancouver og erstattet af en cykel. Belæsset med et telt, en sovepose, en satellittelefon, lidt tøj, mad og vand samt selvfølgelig sit gamle kamera begav Adam Jeppesen sig på den ned langs USA’s vestkyst for at nå frem til Sydamerika.

»Jeg havde ingen planer, andet end at jeg ville se, hvordan naturen er, hvis vi ophæver landegrænser og kulturer – altså fjerner menneskene. Derfor opsøgte jeg den mest utilgængelige natur, bjerge, tørre steder, vildmarken og store skove, hvor man ikke møder mange andre. Alligevel mødte jeg faktisk forbløffende mange på jagt efter sig selv i den store natur. Det er meget moderne, fandt jeg ud af«.

På cyklen var det enkelt og meget mere naturligt at holde mange pauser og stille kameraet, et tysk Lidhof Technica fra 1947, op på sit stativ og tage billeder. Det gjorde Adam Jeppesen kontinuerligt og lagde sine negativer ind mellem de medbragte plader til senere fremkaldelse.

»Ofte gik der mange uger, før jeg kunne gøre noget ved negativerne, og de blev derfor ridsede og støvede. I begyndelsen ærgrede jeg mig over det, men det viste sig at være endnu en af den slags tilfældigheder, der gjorde processen meget bedre. Den stemning, jeg oplevede på rejsen, var, hvad man på engelsk kalder solitude. Det er ikke det samme som ensomhed på dansk, for det bliver alt for tungt. Det at være alene i naturen efter eget valg er noget andet, for der er plads og tid til, at man bliver konfronteret med alt det, man ikke når i hverdagen«.

De første mange dage og nætter i vildmarken var Adam Jeppesen lysvågen, mens lyde fra skove og bjerge trængte gennem teltet. I flere nætter troede han, at en gammel dame gik rundt og skreg omkring ham, men så fandt han ud af, at en gråræv siger sådan.

»Alle sanser er i en form for alarmtilstand, og man er bange. Men efterhånden, som man vænner sig til det og finder ud af, hvad lydene er, slapper man af. Man bliver konfronteret med sig selv – sin angst og al sin tvivl. Det er det mest skræmmende sammen med alle de folk, der har pistoler i USA. Dem var jeg langt mere bange for end dyrene«.

Mange drømmer om at skifte det forjagede og stressede liv ud med en lang periode i naturen, lykkeligt befriet for andre mennesker. Men oplevelsen vil Adam Jeppesen ikke nødvendigvis anbefale.

»Der er en enorm ro i naturen, som gør, at man finder ind i sig selv og for eksempel ikke har dage med dårligt humør. Det kommer jo som regel af andre mennesker. Men for det meste er det jo bare hårdt. Det kan være virkelig svært at komme ud af en sovepose, og man lærer virkelig smagen af instant noodlesog sådan noget at kende. Bagefter sagde jeg til min far, at det hårdeste er alle de ydmygelser, naturen giver én«, forklarer han.

Langt fra Disney

På et tidspunkt sad han flere dage ved bunden af et stort bjerg i Peru og prøvede at overtale sig selv til at cykle op ad det. Det knæ, som senere tvang ham til at stå af cyklen og fortsætte som vandrer, gjorde ondt, og der var ikke flere kræfter.

»Jeg ventede på, at der skulle komme en truck, jeg kunne komme med over bjerget. Men den kom ikke. Der er ingen til at skubbe dig i gang, når du er alene. Så forsvinder noget af den romantiske forestilling. Naturen er helt ligeglad med dig; der er ikke noget Disney over vildmarken«.

Netop naturens rå kræfter er grunden til, at Adam Jeppesen har holdt sine fotos, der alle er taget i farve, i nedtonede nuancer. For at komme tæt på realiteterne.

Rejsen sluttede på Nordpolen for ham for 5 år siden. Dertil kom han med skib, og siden har han arbejdet med sine billeder og er taget tilbage til nogle af stederne for at arbejde sig endnu længere ind i naturen.

»Skulle jeg gøre det igen, ville jeg prøve at blive et sted i stedet for at skulle videre hele tiden. Der kommer spøgelserne virkelig frem fra ens underbevidsthed. Men det er også der, de store spirituelle oplevelser ligger«.

///////////////////////////////////////////

Adam Jeppesen: September 5th (from BO Mulato)

by Susan Tallman, from ART IN PRINT Volume 4, Number 1

Edition Review

As a photographer, Adam Jeppesen is known for large-format, beautifully composed and melancholic pictures. His aesthetic combines sensuous pleasure—his images reward long looking—and emotional distance. The title of his 2008 monograph, Wake, is characteristic in its double entendre: are we meant to read it as verb or noun?

Recently Jeppesen has been scrutinizing the photograph not just as image but as object—an ink and paper thing, made by people and bumping up against the world. The large-scale works of his Flatlands Camp Project are built from photocopies tiled and visibly pinned in place to produce a coherent photographic image that, it is clear, can come apart at any time. His new photogravure series take this notion of the disintegration of the photographic record in a different direction.

For each of 12 sets of prints made in 2013 a single gravure plate was inked once then printed repeatedly, in fainter and fainter iterations, until nothing remained but the plate mark. In some cases there are five images, in others seven or eight, and one plate generated no fewer than twelve impressions before the picture faded from sight.

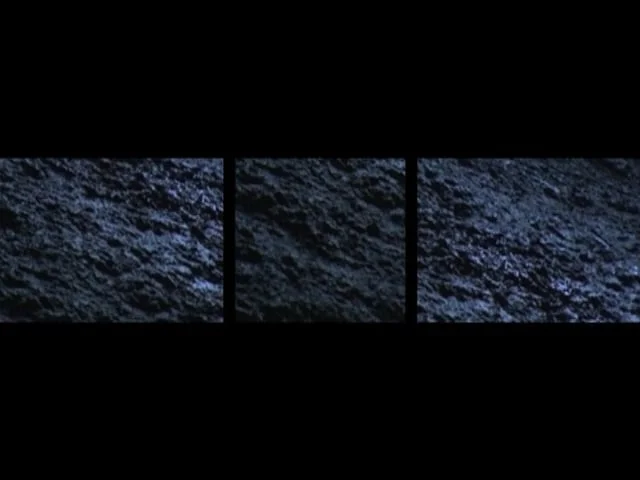

This print-it-till-it-dies device has been used by other artists, but rarely with such poetic resonance. This is partly the result of the Jeppesen workshop’s famously delicate printerly hand and partly to do with the images themselves, which were taken on a 487-day solo trip that Jeppesen made in 2009–2010 from the North American Arctic to the tip of Antarctica. They show open empty places, uninhabited and seemingly uninhabitable: cracked earth stretching to the horizon, rock-strewn desert, barren crumpled ground. While mankind’s handiwork can occasionally be seen (a locomotive, an abandoned shed), people never are. Vast spaces are made intimate: the horizontal plates are modest size and each series is a unique work. This defiance of the multiplicity that photography and photogravure were engineered to produce extends the melancholic disposition of the work: the plate gets just one life.

Jeppesen’s most recent gravure proect, September 5th (from BO Mulato), is different: to begin with, the plate is enormous—nearly six feet high—and though the image of the Bolivian Altiplano gets paler over the course of five impressions, it never fully fades away.

The scale of the prints, combined with the seductive crumble of the photogravure surface, lures the viewer in. Scattered activity in the broad blank sky initially suggests a flock of birds, but is quickly revealed as a concatenation of scratches on the negative, the result of grit in the camera. Close up, the desert disappears into the physical object before us—instead of a picture, we see ink sitting atop paper, the residue of intaglio; we see the photographic grain imposed by the film in Jeppesen’s camera; we see scratches and abrasions, tiny hairs and motes of dust, now as large as the small stones depicted. In short we see a document that charts neither a place nor a moment in time, but a trajectory.

This set, unlike the others, was produced in an edition of five, which makes sense: if the narrative gist of the 2013 series was the irrevocable loss of the past (each is titled with a date, but not a location), this suggests transformation. The moment is irretrievable, the place is distant, the film is damaged, the ink wears away, and yet we get to stand in a gallery looking at magisterial beauty.

Art has its consolations.

//////////////////////////////////////

Maribel García / Adam Jeppesen: The Loneliness of the Traveller

July 2012

Adam Jeppesen’s work challenges the boundaries between documentary and fiction. His photographs inhabit a blurred territory where the real and the tale become interchangeable. Even if the Danish artist seems to remain faithful to what is already in front of his camera, he doesn’t seem to be too concerned about objectivity.

His first monograph, Wake, was published by Steidl in 2008, and brings together a selection of photographs that Jeppesen took over the course of seven years, while traveling on assignment.

The book Wake opens with an air of restlessness. In the first page we see a dead, fallen tree in the middle of a pine forest. Second page, a cupboard with china cups, red drops spilt all over. Then we come across a letter: two people who love each other are apart. Presumably one of them is away, travelling; the other one is waiting at home. One wrote something about a plant dying. The other replied, “I wanna hear yr voice on the phone, maybe t’morrow?” Who knows?

An atmosphere of uncertainty traverses the pages; an expectation in every image, a sense of something happening and yet everything appears so quiet and calm. The quietness is pregnant with discomfort, like an untold story. A mixture of heavy darkness, foggy lights and wet air floats over places, things and living beings. Insignificant objects and situations are invested with a secret narrative that the imagination of the viewer is encouraged to unfold. A plastic chair next to a staircase outside a balcony; an unoccupied table in a restaurant; a crooked letterbox behind a fence in the middle of the night.

Most of the images are pervaded by a sense of loneliness: the loneliness of the traveller. Empty landscapes, empty rooms and empty streets. Only a few living beings are present across the book: the person who writes the letter at the beginning of the book, a dog, a thoughtful woman sat on a table, another woman (or maybe the same, we really can’t tell as her face is turned away from us) standing in front of a mirror and a person lying in the shadows. However, these presences only emphasise the sense of absence. None of them are interacting with the photographer, either because they are ignorant of his presence or just because they are too immersed in their own thoughts to realize that they have company. However it is, their appearance seems to leave with us a stronger feeling of loneliness and distance. It becomes clear from the scarce portraits scattered throughout the narrative that this traveller is an observer, an outsider, a curious soul.

Adam Jepessen’s most recent and ongoing project is called Flatlands Camp Project, and it is essentially the documentation of a solitary journey through the Americas that started in the Arctic and ended in Antarctica over a period of 487 days.

Most of the images within this project are landscapes: the vast land lying at the feet of the adventurer. Horizons, kilometres of deserted earth and sea. Traces of the journey are present in the photographs: scratches, stains and dust that remained on the surface of the negative as the traveller carried them all the way through his expedition. Traces that invest the photographs with a sense of physicality and tell us about the journey as much as the images themselves do. Through them, we feel the tiredness and the struggle of the traveller making his way through foreign territory.

The narrative is serene and slow; as with his previous work, what we see is filled with an uncanny atmosphere. There is always the same sense of absence hovering over the desolated landscapes, the empty territories and the incommensurable and secretive nature. In fact, this work could make us think of those Romantic figures in Friedrich’s paintings, with their backs to us, contemplating in a sort of ecstasy the sublime beauty of nature. However, this time we don’t see the back of the traveller but we are instead allowed straight into his eyes, staring into the raw eternity of an agitated sea.

In Flatlands Camp Project the only human presence is the one of the photographer himself, the lonely witness of his own journey. Usually blurred and undefined, his presence is diffused and ghostly or half concealed, as though about to vanish. It seems as if that diluted figure that he offers as a self-portrait serves as a metaphor to represent the fluid character of his work, sharing with us a flowing and open narrative free from the burdens of truth and objectivity.

But Flatlands Camp Project is much more than a mere group of documentary images about a trip. Because of the way the artist conceives his work, the way he produces it and the way he chooses to show it and install it (deconstructing the image into different pieces, then assembling them back together with pins), his art reaches out from the boundaries of photography and makes an incursion into those of performance and sculpture. The photographs in Jeppesen’s project became an artistic object that can’t be isolated from the way the artist produces them, constructs them and displays them.

Going through Adam Jeppesen’s work is like embarking in a mental journey. It doesn’t teach us anything, but encourages us to feel. His photographs don’t give us any facts. Even if they are the product of a trip, they don’t tell us about people, places or foreign cultures and traditions the way we expect travel photography to. In fact, we are unable to tell where each photograph was taken, as the artist doesn’t give us any information about it. However, looking at these images, we still feel the power of the journey, the amazement of the traveller, the nostalgia and the mystery while staring into never ending horizons. And this is where the magic of these photographs resides. This traveller is a dreamer, with the sensitivity of an artist engaged with beauty and adventure. And by going into his images, so are we.

///////////////////////////////////////

Essay by William Pym

The work of Adam Jeppesen invites thoughts about the origins and the future of the documentary photographer – perhaps social photographer is the word I’d rather use – the kind of artist who does not ostensibly stage the world, but prefers to watch it, then frame it as it is. The only act of manipulation, the only insertion of opinion, comes as the artist’s eye decides what will fit inside the rectangle of the aperture; the rest is already there.

It used to be as simple as that. Modern socio-documentary photography blossomed at the beginning of the last century because it was unburdened by the dizzy questions that confronted, say, the painter trying to produce work after Cézanne and Picasso. While the painter’s world grew ever more complicated, the socio-documentary photographer’s, in its relative infancy, became cleaner and more focused. As soon as August Sander embarked on his Westerwald project, “Man of the Twentieth Century”, in 1909, he cleared a simple path for himself and his life’s work. His concept was to photograph every kind of person living in his small community outside Cologne, and the simplicity of the project gave the work room to take on great nuance and complexity as the years went by. It is art photography that obeys a basic logic, but isn’t small-minded. It grows. And it stands up: Sander’s reputation is as tidy today as it has ever been. A few years later in America – amazingly so considering George W. Bush’s apparent total antipathy to the arts – FDR’s Farm Security Administration underwrote documentary photography of the great depression. Walker Evans and Berenice Abbot had the means to look and look again, at people and places, to create a body of work whose biggest statement was of accumulation, of continuation. Resign yourself to the infinity of the subject matter, and keep going. It keeps growing.

The bullish tide of attitude in art in the second half of the 20th Century, the idea that the artist’s personality was important enough that it should be visible in the frame, meant that the pacifism of Sander, say, might not be fast and fierce enough for the modern world. Take the warped documentary of Philip Lorca Di-Corcia who is hugely popular amongst students these days and molding a few of them over at Yale University as we speak. The flare of a Hollywood spotlight on the man walking down the street is loud and invasive because diCorcia wants to muscle in and refine the image. He sees himself in a saturated, noisy world, and he wants some control. He must wrangle and fight in the frame. If he doesn’t, he will not have left his mark.

So this is one destination for Sander’s freedom, 100 years later. Sanders’ was a working practice without attitude or explicit commentary and, well, that means there was lots of room for the opportunistic or needy contemporary artist to put themself inside the picture and really explore and expose themselves. His vision has been hijacked in a way to suit modern tastes. It’s not a criticism per se, just a symptom of one contemporary artistic mentality. Exhibitionism/confession/solipsism is popular today. Hence it’s lucrative and hence, in the eyes of some, it is to be heartily encouraged.

From what I’ve seen and the few things I’ve heard from my minimal, liminal communications with Adam Jeppesen, he possesses a very different mentality, and one that I am enthusiastic to champion. His is a truer evolution of Sander’s spirit, and one that will prove useful in the years ahead. Jeppesen gives in to vision, by which I don’t mean his grand artistic vision, but simply what he sees around. He sacrifices himself to the apprenticeship of seeing, in confidence that the world will begin to order itself in front of him.

There is no thematic thread, no personal agenda pawing to be let in at the corners of the frame. He shows no desire to be in there, because the fundamental joy of seeing begs for humility and silence. A longer, larger, richer picture is coming into focus.There are no geographical markers in Jeppesen’s photographs. There is no clear text, no giveaway ethnicity or landmark that places the picture on the map. Human characters move slowly and deliberately if they move at all, and they don’t interact with one another. Technology is often present, often looming large, but humans do not interact with it. There’s no palpable enjoyment in that relationship. Perhaps this sounds very drab. Do let me tell you where the action is.

Humans live in a world where they are isolated, flanked by nature on one side and technology on the other. Jeppesen’s photographs show man in the middle, finding a place to balance in this world, a beautiful world: the modern world. Man’s creations and the creature that is nature are too overwhelming, too amorphous, too unpredictable, to understand instinctively. By surrendering wholeheartedly to vision, the artist cannot hatch and control a snappy method of categorizing and capturing the world. But this sacrifice is worthwhile. The only universals that Jeppesen can be completely sure about are light and air, and these are the most consistent, most reliable characters in his work. Light and air suffuse his pictures and have a depth of personality that a portrait photographer would murder for. The atmosphere’s temperament is finely-tuned: in a greenhouse-style travel terminal the air is overcooked and the light is trapped; in the mountain range the mist has a cleansing, restorative taste; above the clean, young city the air is thinner and the ultramodern buildings more crisply in focus. Light and air touch everything; this ether connects everything and everyone to everything and everyone else.

This inescapable sense of a global ecology offers security. Feelings of isolation will subside as long as we can remember that everything feeds from the same source. “Art, or what we call that, you can love it or appreciate it, but you can’t really talk about it. Doesn’t make any sense.” This comes from William Eggleston, a photographer who Jeppesen naturally evokes; he has made rambling, anonymous, wondrous work for 40 years that explains the mechanics of the gigantic American south better than any other. Maybe so, but you can talk about the beauty that the world has always possessed, and you can talk about the beauty you plan to see, and to create. As technology effortlessly makes the world smaller, turning yesterday’s intangibles into reality in the blink of an eye, a photographer talking about anything less is as irrelevant as he is irresponsible. I strongly suspect Adam Jeppesen is neither of these things.

William Pym

August 28th-December 12th, 2005

Philadelphia, USA

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Text for Flatlands Camp Project: Beyoner at Galleri Peter Lav 2011

In the middle of 2009 Adam Jeppesen began a period of uninterrupted, unaccompanied travel that lasted for 487 days. He traveled on a continuous grade, in one direction, constantly, on the ground, from the Arctic to Antarctica through the Americas.

During this period, the artist grew distant from the validation of other people and the convenient markers of cultured society. The long, solitary trip took him progressively further from a traditional understanding of space and time. Only his photographs, he says, became a means of “guaranteeing a present.” From day to day, the camera received the artist’s experiences and confirmed them to him.

Jeppesen has become known, over the past decade, for a body of work that is both meticulously edited and nakedly diaristic. The artist’s distinctive style, which crystallized in his first major monograph, Wake (Steidl, 2008), located a space in between documentary and dream.

Nostalgia remains important to Jeppesen, and many aesthetic decisions are still made by remembering, projecting and dreaming. The works emerging from his most recent travels, however, are primarily concerned with direct, immediate responses. This need for straight confirmation was borne of human necessity as the artist burrowed deeper than ever before into a dreamlike state.

Some of the pictures are far from pristine. Grit jiggling in a box has gnawed the surface of certain negatives, leaving scuffs of evidence on the final prints that speak to the extended physical journey that the work shared with the artist. The occasional occurrences that most photographers will trash, such as light leaks and odd exposures, are allowed to live. Certain shots flirt with total abstraction. At the printing end of the process, Jeppesen is experimenting with unconventional, offhand and ephemeral techniques. The artist is keen to question the authority of the print, the end result, the expected conclusion of the photographic act.

Because what is an end result? These works appear to ask what an image is worth, what a moment is worth, and what a memory is worth. What were these experiences? Jeppesen fastidiously avoids the fetishized travel narrative. Location and context are irrelevant. So what was important about these experiences? What is most relevant for this particular body of work, it seems, is the very act of experiencing something. “The Flatlands Camp Project,” which will evolve dramatically over the course of the next year, aspires to become an experience of its own.

////////////////////////////////////////////////

Text by Doug Rickard, American Suburb X